The Tang Dynasty (618–907) marked one of the most prosperous economic periods in Chinese history. From post-war recovery to sustained growth and eventual transformation, Tang social economy laid the material foundation for political stability, military strength, and cultural flourishing. In particular, the Zhenguan era and the Kaiyuan Golden Age represented the peak of economic development in the early Tang period.

Agricultural Recovery and Expansion

Following the collapse of the Sui Dynasty, agricultural productivity across China had been severely damaged by prolonged warfare. After reunifying the empire, Tang emperors placed agriculture at the center of national policy.

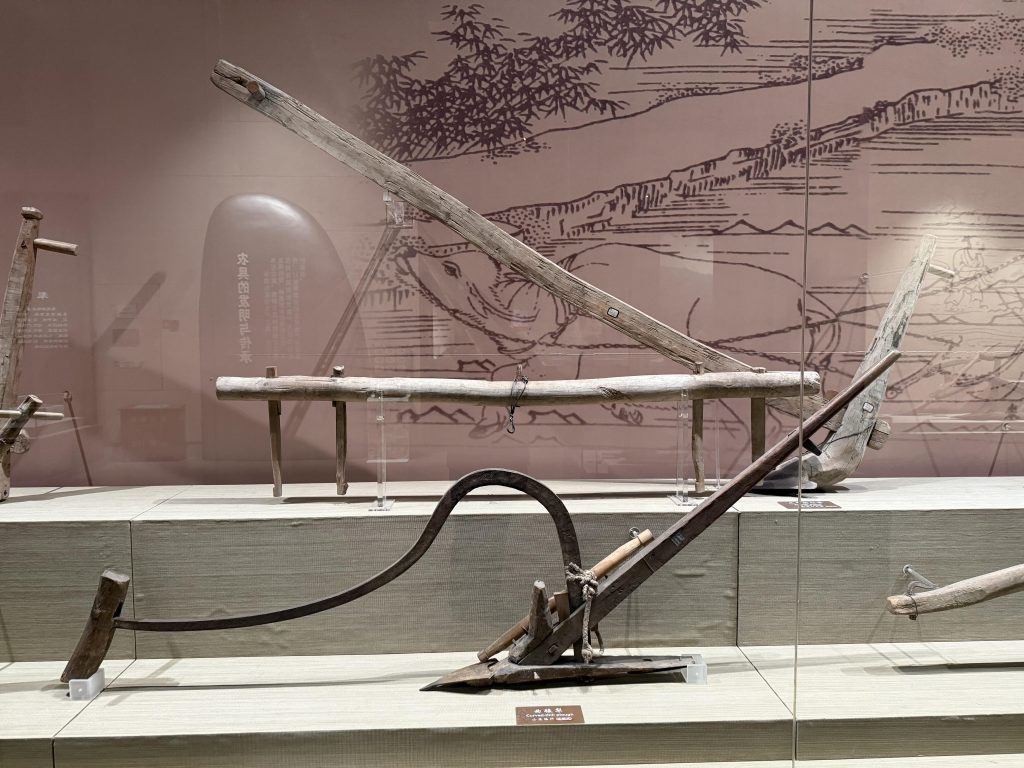

A series of reforms were implemented, including the Land Equalization System (Juntian System) and the Zuyongdiao Tax System, which significantly reduced the burden on peasants and improved production efficiency. At the same time, advances in farming tools, cultivation techniques, and large-scale irrigation projects greatly boosted agricultural output.

As a result, agricultural production expanded rapidly during the Zhenguan period and reached unprecedented levels in the Kaiyuan era, providing a solid economic base for the Tang state.

Prosperity of the Handicraft Industry

Agricultural surplus released a large amount of labor, accelerating the growth of the handicraft industry. In terms of technology, production scale, and variety, Tang handicrafts surpassed those of previous dynasties.

The textile industry, especially silk weaving, achieved a high level of refinement and technical sophistication. The ceramic industry entered a new stage of development, producing celadon, white porcelain, and the famous Tang Tri-colored Glazed Pottery (Tang Sancai). Other industries—including papermaking, tea processing, metallurgy, and shipbuilding—also flourished, reflecting the advanced level of Tang manufacturing.

Commercial Development and Foreign Trade

The rapid progress of agriculture and handicrafts fueled the prosperity of domestic commerce and international trade. A wide range of commodities circulated in markets, including grain, salt, tea, textiles, medicine, precious metals, and daily goods.

Major commercial centers emerged across the empire, such as Chang’an (modern Xi’an), Luoyang, Chengdu, Hangzhou, Lanzhou, and Guilin. These cities established regulated markets with strict administrative oversight, ensuring stable commercial operations.

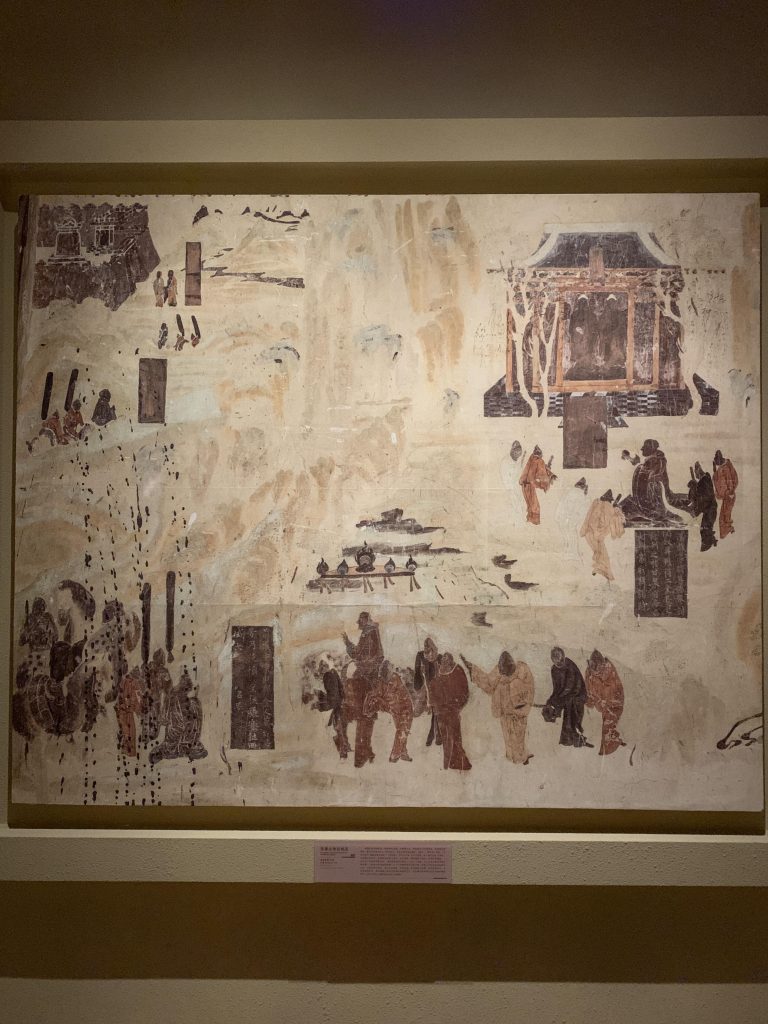

On the international front, the Tang Dynasty benefited from the continued operation of the Silk Road, attracting large numbers of foreign merchants and envoys. Meanwhile, maritime trade expanded rapidly. Tang ships sailed across the Indian Ocean and reached the Persian Gulf, facilitating frequent exchanges with regions in Asia and Africa and positioning Tang China as a global trading power.

Economic Transformation in the Late Tang Period

The outbreak of the An Lushan Rebellion dealt a severe blow to the Tang economy. Traditional systems such as the Land Equalization System and the Zuyongdiao Tax System gradually collapsed. To address mounting fiscal difficulties, the government introduced the Double Tax System, which levied taxes based on property and wealth. This reform helped restore state revenue and influenced later Chinese tax systems.

Widespread warfare in northern China also triggered large-scale population migration to the Yangtze River Basin, bringing labor and advanced production techniques to southern regions. Consequently, the economic center of China gradually shifted southward. Agriculture, handicrafts, and commerce in southern China surpassed those in the north, and new urban and suburban commercial hubs emerged.

Notably, early forms of exchange and financial systems appeared during this period, indicating that China’s commodity economy had entered a more advanced stage.

Historical Significance

Overall, the social economy of the Tang Dynasty was characterized by strong agricultural foundations, advanced handicraft production, and extensive domestic and international trade. These economic achievements supported the empire’s golden age and reshaped China’s long-term economic geography, leaving a lasting impact on subsequent dynasties.